Python reticulatus

Python reticulatus

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Reptilia

Order: Squamata

Suborder: Serpentes

Family: Pythonidae

Genus: Python

Species: P. reticulatus

Binomial name

Python reticulatus

(Schneider, 1801)

Python reticulatus

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Reptilia

Order: Squamata

Suborder: Serpentes

Family: Pythonidae

Genus: Python

Species: P. reticulatus

Binomial name

Python reticulatus

(Schneider, 1801)

Python reticulatus, also known as the (Asiatic) reticulated python, is a species of python found in Southeast Asia. Adults can grow to 6.95 m (22.8 ft) in length but normally grow to an average of 3–6 m (10–20 ft). They are the world's longest snakes and longest reptile, but are not the most heavily built. Like all pythons, they are nonvenomous constrictors and normally not considered dangerous to humans. Although large specimens are powerful enough to kill an adult human, attacks are only occasionally reported.

An excellent swimmer, Python reticulatus has been reported far out at sea and has colonized many small islands within its range. The specific name, reticulatus, is Latin meaning "net-like", or reticulated, and is a reference to the complex color pattern.

Contents

1 Description

2 Geographic range

3 Habitat

4 Feeding

5 Danger to humans

6 Reproduction

7 Captivity

8 Taxonomy

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

An excellent swimmer, Python reticulatus has been reported far out at sea and has colonized many small islands within its range. The specific name, reticulatus, is Latin meaning "net-like", or reticulated, and is a reference to the complex color pattern.

Contents

1 Description

2 Geographic range

3 Habitat

4 Feeding

5 Danger to humans

6 Reproduction

7 Captivity

8 Taxonomy

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Description

This species is the largest snake native to Asia. In general, reticulated pythons with lengths of more than 6 m (20 ft) are rare, though according to the Guinness Book of World Records it is the only existent snake to regularly exceed that length. One of the largest scientifically measured specimens, which was from Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, was measured under anesthesia at 6.95 m (22.8 ft) and weighed 59 kg (130 lb) after not having eaten for 3 months. Widely published data of specimens that were reported to be several feet longer have not been confirmed.

Even what was widely accepted as the largest ever "accurately" measured snake, that being Colossus, a male kept at the Highland Park Zoo (now Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania during the 1950s and early 1960s, with a peak reported length of 8.7 m (29 ft), recently turned out to be wrong. When Colossus died, April 14, 1963, its body was deposited in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. At that time its skeleton was measured and found to be 20 ft 10 in (6.35 m) in total length, significantly shorter than the measurements previously published by Barton and Allen. Apparently, they had been adding a few extra feet to the measurements to compensate for "kinks", since it is virtually impossible to completely straighten an extremely large live python. Too large to be preserved with formaldehyde and then stored in alcohol, the specimen was instead prepared as a dis-articulated skeleton. The hide was sent to a laboratory to be tanned, and unfortunately it was either lost or destroyed.

This species is the largest snake native to Asia. In general, reticulated pythons with lengths of more than 6 m (20 ft) are rare, though according to the Guinness Book of World Records it is the only existent snake to regularly exceed that length. One of the largest scientifically measured specimens, which was from Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, was measured under anesthesia at 6.95 m (22.8 ft) and weighed 59 kg (130 lb) after not having eaten for 3 months. Widely published data of specimens that were reported to be several feet longer have not been confirmed.

Even what was widely accepted as the largest ever "accurately" measured snake, that being Colossus, a male kept at the Highland Park Zoo (now Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania during the 1950s and early 1960s, with a peak reported length of 8.7 m (29 ft), recently turned out to be wrong. When Colossus died, April 14, 1963, its body was deposited in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. At that time its skeleton was measured and found to be 20 ft 10 in (6.35 m) in total length, significantly shorter than the measurements previously published by Barton and Allen. Apparently, they had been adding a few extra feet to the measurements to compensate for "kinks", since it is virtually impossible to completely straighten an extremely large live python. Too large to be preserved with formaldehyde and then stored in alcohol, the specimen was instead prepared as a dis-articulated skeleton. The hide was sent to a laboratory to be tanned, and unfortunately it was either lost or destroyed.

Numerous reports have been made of larger snakes, but since none of these has been measured by a scientist nor have the specimens been deposited at a museum, they must be regarded as unproven and possibly erroneous. In spite of what was for many years a standing offer of $50,000 for a live, healthy snake over 9.1 m (30 ft) long by the New York Zoological Society (NYZS), known since 1993 as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), no attempt to claim this reward was ever made.

The color pattern is a complex geometric pattern that incorporates different colors. The back typically has a series of irregular diamond shapes, flanked by smaller markings with light centers. In this species' wide geographic range, much variation of size, color, and markings commonly occurs.

In zoo exhibits the color pattern may seem garish, but in a shadowy jungle environment amid fallen leaves and debris it allows them to virtually disappear. Called a disruptive coloration, it protects them from predators and helps them to catch their prey.

The color pattern is a complex geometric pattern that incorporates different colors. The back typically has a series of irregular diamond shapes, flanked by smaller markings with light centers. In this species' wide geographic range, much variation of size, color, and markings commonly occurs.

In zoo exhibits the color pattern may seem garish, but in a shadowy jungle environment amid fallen leaves and debris it allows them to virtually disappear. Called a disruptive coloration, it protects them from predators and helps them to catch their prey.

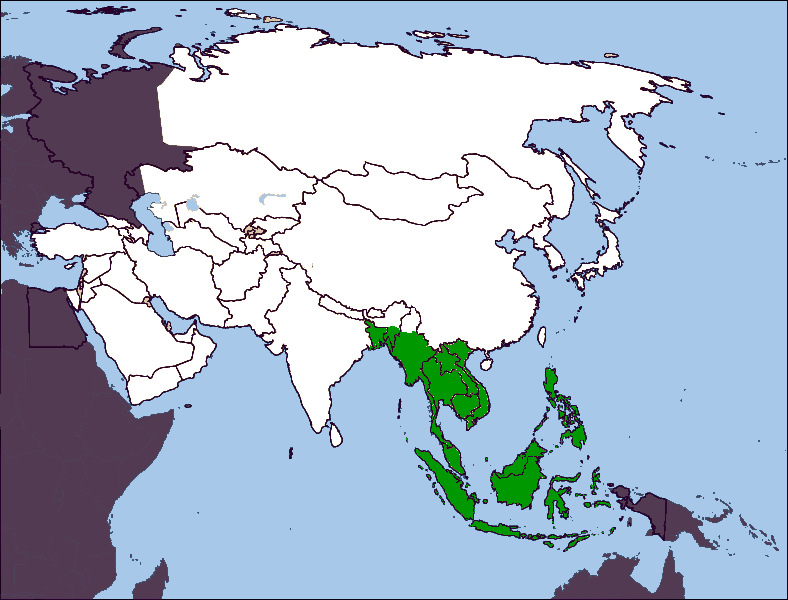

Geographic range

Reticulated pythons are found in Southeast Asia

from the Nicobar Islands, northeast India, Bangladesh,

Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia and

Singapore, east through Indonesia and the Indo-Australian

Archipelago (Sumatra, the Mentawai Islands, the Natuna

Islands, Borneo, Sulawesi, Java, Lombok, Sumbawa, Sumba,

Flores, Timor, Maluku, Tanimbar Islands) and the Philippines

(Basilan, Bohol, Cebu, Leyte, Luzon, Mindanao, Mindoro,

Negros, Palawan, Panay, Polillo, Samar, Tawi-Tawi).

The original description does not include a type locality.

Restricted to "Java" by Brongersma (1972).

Three subspecies have been proposed, but are not recognised

in the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

The color and size can vary a great deal among the subspecies

described. Geographical location is a good key to establishing

the subspecies, as each one has a distinct geographical range.

Habitat

The reticulated python lives in rain forests, woodlands, and nearby grasslands. It is also associated with rivers and is found in areas with nearby streams and lakes. An excellent swimmer, it has even been reported far out at sea and has consequently colonised many small islands within its range. During the early years of the twentieth century it is said to have been common even in busy parts of Bangkok, sometimes eating domestic animals.

Feeding

Their natural diet includes mammals and occasionally birds. Small specimens up to 3–4 m (10–14 ft) long eat mainly rodents such as rats, whereas larger individuals switch to prey such as Viverridae (e.g. civets and binturongs), and even primates and pigs. Near human habitation, they are known to snatch stray chickens, cats and dogs on occasion. Among the largest, fully documented prey items to have been taken are a half-starved Sun Bear of 23 kilograms that was eaten by a 6.95 m (23 ft) specimen and took some ten weeks to digest, as well as pigs of more than 60 kg (132 lb). As a rule of thumb, these snakes seem able to swallow prey up to ¼ their own length, and up to their own weight. As with all pythons, they are primarily ambush hunters, usually waiting until prey wanders within strike range before seizing it in their coils and killing via constriction. However, there is at least one documented case of a foraging python entering a forest hut and taking a child.

Reticulated pythons are found in Southeast Asia

from the Nicobar Islands, northeast India, Bangladesh,

Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia and

Singapore, east through Indonesia and the Indo-Australian

Archipelago (Sumatra, the Mentawai Islands, the Natuna

Islands, Borneo, Sulawesi, Java, Lombok, Sumbawa, Sumba,

Flores, Timor, Maluku, Tanimbar Islands) and the Philippines

(Basilan, Bohol, Cebu, Leyte, Luzon, Mindanao, Mindoro,

Negros, Palawan, Panay, Polillo, Samar, Tawi-Tawi).

The original description does not include a type locality.

Restricted to "Java" by Brongersma (1972).

Three subspecies have been proposed, but are not recognised

in the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

The color and size can vary a great deal among the subspecies

described. Geographical location is a good key to establishing

the subspecies, as each one has a distinct geographical range.

Habitat

The reticulated python lives in rain forests, woodlands, and nearby grasslands. It is also associated with rivers and is found in areas with nearby streams and lakes. An excellent swimmer, it has even been reported far out at sea and has consequently colonised many small islands within its range. During the early years of the twentieth century it is said to have been common even in busy parts of Bangkok, sometimes eating domestic animals.

Feeding

Their natural diet includes mammals and occasionally birds. Small specimens up to 3–4 m (10–14 ft) long eat mainly rodents such as rats, whereas larger individuals switch to prey such as Viverridae (e.g. civets and binturongs), and even primates and pigs. Near human habitation, they are known to snatch stray chickens, cats and dogs on occasion. Among the largest, fully documented prey items to have been taken are a half-starved Sun Bear of 23 kilograms that was eaten by a 6.95 m (23 ft) specimen and took some ten weeks to digest, as well as pigs of more than 60 kg (132 lb). As a rule of thumb, these snakes seem able to swallow prey up to ¼ their own length, and up to their own weight. As with all pythons, they are primarily ambush hunters, usually waiting until prey wanders within strike range before seizing it in their coils and killing via constriction. However, there is at least one documented case of a foraging python entering a forest hut and taking a child.

Danger to humans

Attacks on humans are rare, but this species has been responsible for several human fatalities, in both the wild and captivity. They are among the few snakes that have been fairly reliably reported to eat people, although only a few cases of the snake actually eating (rather than just killing) a human appear to be authenticated:

Two incidents, apparently in early 20th century Indonesia: On Salibabu, a 14-year-old boy was killed and supposedly eaten by a specimen 5.17 m (c.17 ft) in length. Another incident involved an adult woman reputedly eaten by a "large reticulated python", but few details are known.

Franz Werner reported a case from Burma occurring either in the early 1910s or in 1927.A jeweller named Maung Chit Chine, who went hunting with his friends, was apparently eaten by a 6 m (20 ft.) specimen after he sought shelter from a rainstorm in or under a tree. Supposedly, he was swallowed feet-first, contrary to normal snake behavior, but perhaps the easiest way for a snake to actually swallow a human.

In 1932, Frank Buck wrote about a teenage boy who was eaten by a pet 25 ft (7.6 m). reticulated python in the Philippines. According to Buck, the python escaped, and when it was found, a human child's shape was recognised inside the snake. It turned out to be the son of the snake's owner.

Among a small group of Agta negritos in the Philipppines, six deaths by python have been documented within a period of 40 years, plus one who died later of an infected bite.

On September 4, 1995, Ee Heng Chuan, a 29-year-old rubber tapper from the southern Malaysian state of Johor, was killed by a large reticulated python. The victim had apparently been caught unaware and was squeezed to death. The snake had coiled around the lifeless body with the victim's head gripped in its jaws when it was stumbled upon by the victim's brother. The python, measuring 23 ft (7.0 m) long and weighing more than 300 lb, was killed soon after by the arriving police, who required four shots to bring it down.

According to Mark Auliya, the corpse of 32-year-old Mangyan, Lantod Gumiliu, was recovered from the belly of a 7 m (23 ft) reticulated python on Mindoro, probably in January, 1998.

On October 23, 2008, a 25-year-old Virginia Beach, Virginia woman, Amanda Ruth Black, appeared to have been killed by a 13-foot (4.0 m) pet reticulated python. The apparent cause of death was asphyxiation. The snake was later found in the bedroom in an agitated state.

On January 21, 2009, a 3-year-old Las Vegas boy was wrapped by an 18-foot (5.5 m) pet reticulated python, turning blue. The boy's mother, who had been babysitting the python on behalf of a friend, rescued the toddler by gashing the python with a knife. The snake was later euthanized because of its fatal wounds.

Considering the known maximum prey size, it is technically possible for a full-grown specimen to open its jaws wide enough to swallow a human child, teenager, or even an adult, although the flaring shoulders of Homo sapiens could pose a problem for a snake with insufficient size. The victim would almost certainly be dead by the time the snake started swallowing.

Attacks on humans are rare, but this species has been responsible for several human fatalities, in both the wild and captivity. They are among the few snakes that have been fairly reliably reported to eat people, although only a few cases of the snake actually eating (rather than just killing) a human appear to be authenticated:

Two incidents, apparently in early 20th century Indonesia: On Salibabu, a 14-year-old boy was killed and supposedly eaten by a specimen 5.17 m (c.17 ft) in length. Another incident involved an adult woman reputedly eaten by a "large reticulated python", but few details are known.

Franz Werner reported a case from Burma occurring either in the early 1910s or in 1927.A jeweller named Maung Chit Chine, who went hunting with his friends, was apparently eaten by a 6 m (20 ft.) specimen after he sought shelter from a rainstorm in or under a tree. Supposedly, he was swallowed feet-first, contrary to normal snake behavior, but perhaps the easiest way for a snake to actually swallow a human.

In 1932, Frank Buck wrote about a teenage boy who was eaten by a pet 25 ft (7.6 m). reticulated python in the Philippines. According to Buck, the python escaped, and when it was found, a human child's shape was recognised inside the snake. It turned out to be the son of the snake's owner.

Among a small group of Agta negritos in the Philipppines, six deaths by python have been documented within a period of 40 years, plus one who died later of an infected bite.

On September 4, 1995, Ee Heng Chuan, a 29-year-old rubber tapper from the southern Malaysian state of Johor, was killed by a large reticulated python. The victim had apparently been caught unaware and was squeezed to death. The snake had coiled around the lifeless body with the victim's head gripped in its jaws when it was stumbled upon by the victim's brother. The python, measuring 23 ft (7.0 m) long and weighing more than 300 lb, was killed soon after by the arriving police, who required four shots to bring it down.

According to Mark Auliya, the corpse of 32-year-old Mangyan, Lantod Gumiliu, was recovered from the belly of a 7 m (23 ft) reticulated python on Mindoro, probably in January, 1998.

On October 23, 2008, a 25-year-old Virginia Beach, Virginia woman, Amanda Ruth Black, appeared to have been killed by a 13-foot (4.0 m) pet reticulated python. The apparent cause of death was asphyxiation. The snake was later found in the bedroom in an agitated state.

On January 21, 2009, a 3-year-old Las Vegas boy was wrapped by an 18-foot (5.5 m) pet reticulated python, turning blue. The boy's mother, who had been babysitting the python on behalf of a friend, rescued the toddler by gashing the python with a knife. The snake was later euthanized because of its fatal wounds.

Considering the known maximum prey size, it is technically possible for a full-grown specimen to open its jaws wide enough to swallow a human child, teenager, or even an adult, although the flaring shoulders of Homo sapiens could pose a problem for a snake with insufficient size. The victim would almost certainly be dead by the time the snake started swallowing.

Reproduction

Oviparous, females lay between 15 and 80 eggs per clutch. At an optimum incubation temperature of 31–32 °C (88–90 °F), the eggs take an average of 88 days to hatch. Hatching are at least 2 feet (61 cm) in length, and smaller for dwarf species.

Captivity

Increased popularity in the pet trade is due largely to increased

efforts in captive breeding and selectively bred mutations such as

the "albino" and "tiger" strains. They can make good captives, but

keepers should have previous experience with such large constrictors

to ensure safety to both animal and keeper. Although their

interactivity and beauty draws much attention, some feel

they are unpredictable. They do not attack humans by

nature, but will bite and possibly constrict if they feel threatened,

or mistake a hand for food. While not venomous,

large pythons can inflict serious injuries, sometimes requiring stitches.

The huge size and attractive pattern of these snakes has made

them favorite zoo exhibits, with several individuals claimed to be

above 20 ft (6.1 m) in length and more than one claimed to be

the largest in captivity. However, due to their huge size,

immense strength, aggressive disposition, and the mobility of

the skin relative to the body, it is very difficult to get exact

length measurements on a living reticulated python, and weights

are rarely indicative, as captive pythons are often obese. Claims

made by zoos and animal parks are sometimes exaggerated,

such as the claimed 15 m (49 ft) snake in Indonesia which was

subsequently proven to be less than 23 feet (7.0 m) long. For

this reason, scientists do not accept the validity of length

measurements unless performed on a dead or anesthetized snake

which is later preserved in a museum collection. There are now

"super dwarf" reticulated pythons from some islands north west

of Australia where the adults rarely get more than 15 feet

(4.6 m) long, and are being bred to be much smaller. Males can

be at most 5 feet (1.5 m) long, females a little longer.

Oviparous, females lay between 15 and 80 eggs per clutch. At an optimum incubation temperature of 31–32 °C (88–90 °F), the eggs take an average of 88 days to hatch. Hatching are at least 2 feet (61 cm) in length, and smaller for dwarf species.

Captivity

Increased popularity in the pet trade is due largely to increased

efforts in captive breeding and selectively bred mutations such as

the "albino" and "tiger" strains. They can make good captives, but

keepers should have previous experience with such large constrictors

to ensure safety to both animal and keeper. Although their

interactivity and beauty draws much attention, some feel

they are unpredictable. They do not attack humans by

nature, but will bite and possibly constrict if they feel threatened,

or mistake a hand for food. While not venomous,

large pythons can inflict serious injuries, sometimes requiring stitches.

The huge size and attractive pattern of these snakes has made

them favorite zoo exhibits, with several individuals claimed to be

above 20 ft (6.1 m) in length and more than one claimed to be

the largest in captivity. However, due to their huge size,

immense strength, aggressive disposition, and the mobility of

the skin relative to the body, it is very difficult to get exact

length measurements on a living reticulated python, and weights

are rarely indicative, as captive pythons are often obese. Claims

made by zoos and animal parks are sometimes exaggerated,

such as the claimed 15 m (49 ft) snake in Indonesia which was

subsequently proven to be less than 23 feet (7.0 m) long. For

this reason, scientists do not accept the validity of length

measurements unless performed on a dead or anesthetized snake

which is later preserved in a museum collection. There are now

"super dwarf" reticulated pythons from some islands north west

of Australia where the adults rarely get more than 15 feet

(4.6 m) long, and are being bred to be much smaller. Males can

be at most 5 feet (1.5 m) long, females a little longer.

Taxonomy

Three subspecies may be encountered, including two new ones:

P. r. reticulatus, Schneider (1801) – Called "retics" in herpetoculture.

P. r. jampeanus, Auliya et al. (2002) – Kayaudi dwarf reticulated pythons or Jampea retics, about half the length, or according to Auliya et al. (2002), not reaching much more than 2 m in length. Found on Tanahjampea in the Selayar Archipelago south of Sulawesi. Closely related to P. r. reticulatus of the Lesser Sundas.

P. r. saputrai, Auliya et al. (2002) – Selayer reticulated pythons or Selayer retics. Found on Selayar Island in the Selayar Archipelago and also adjacent Sulawesi. This subspecies represents a sister lineage to all other populations of reticulated pythons tested. According to Auliya et al. (2002) it does not exceed 4 m in length.

The latter two are dwarf subspecies. Apparently, the population of the Sangihe Islands north of Sulawesi represents another such subspecies which is basal to the P. r. reticulatus plus P. r. jampeanus clade, but it is not yet formally described.

The proposed subspecies dalegibbonsi, euanedwardsi, haydnmacphiei, neilsonnemani, patrickcouperi and stuartbigmorei have not found general acceptance.

A recent phylogenetic study of pythons suggested that the reticulated python as well as the Timor python are more closely related to Australasian pythons than other members of the genus Python. Reynolds et al.[3] described the genus Malayopython for this species and its sister species, the Timor python, M. timoriensis.

Three subspecies may be encountered, including two new ones:

P. r. reticulatus, Schneider (1801) – Called "retics" in herpetoculture.

P. r. jampeanus, Auliya et al. (2002) – Kayaudi dwarf reticulated pythons or Jampea retics, about half the length, or according to Auliya et al. (2002), not reaching much more than 2 m in length. Found on Tanahjampea in the Selayar Archipelago south of Sulawesi. Closely related to P. r. reticulatus of the Lesser Sundas.

P. r. saputrai, Auliya et al. (2002) – Selayer reticulated pythons or Selayer retics. Found on Selayar Island in the Selayar Archipelago and also adjacent Sulawesi. This subspecies represents a sister lineage to all other populations of reticulated pythons tested. According to Auliya et al. (2002) it does not exceed 4 m in length.

The latter two are dwarf subspecies. Apparently, the population of the Sangihe Islands north of Sulawesi represents another such subspecies which is basal to the P. r. reticulatus plus P. r. jampeanus clade, but it is not yet formally described.

The proposed subspecies dalegibbonsi, euanedwardsi, haydnmacphiei, neilsonnemani, patrickcouperi and stuartbigmorei have not found general acceptance.

A recent phylogenetic study of pythons suggested that the reticulated python as well as the Timor python are more closely related to Australasian pythons than other members of the genus Python. Reynolds et al.[3] described the genus Malayopython for this species and its sister species, the Timor python, M. timoriensis.

Growth Comparisons of Dwarf Retics

In 2005 David Bellis, a hobbiest keeper, took it upon himself to investigate theories surrounding the growth rates of “dwarf” retics on a period of six months. While not a scientific experiment the results are certainly intriguing and provide an insight into the viability of food related theories surrounding these fascinating sub-species.

He decided that in order to make his test as fair as possible he needed to establish a test group of rough approximate age containing both dwarf and mainland type retics. This test group was established using 3 “Super Dwarf” retics and a single mainland retic (an Amel tiger). All of these animals were born early to mid May in 2005.

In order to look at growth rates the logical factor to alter was the diet. As a result one “Super Dwarf” (Animal A) was fed once every other week, one “Super Dwarf” (Animal B) was fed once a week, one “Super Dwarf” (Animal C) was fed twice a week, and the Mainland (Animal D) was fed once a week. All meals were approximately 25% of the animals body weight.

Animals A, B, C and D are always displayed from left to right in the below photographs with the tables.

In 2005 David Bellis, a hobbiest keeper, took it upon himself to investigate theories surrounding the growth rates of “dwarf” retics on a period of six months. While not a scientific experiment the results are certainly intriguing and provide an insight into the viability of food related theories surrounding these fascinating sub-species.

He decided that in order to make his test as fair as possible he needed to establish a test group of rough approximate age containing both dwarf and mainland type retics. This test group was established using 3 “Super Dwarf” retics and a single mainland retic (an Amel tiger). All of these animals were born early to mid May in 2005.

In order to look at growth rates the logical factor to alter was the diet. As a result one “Super Dwarf” (Animal A) was fed once every other week, one “Super Dwarf” (Animal B) was fed once a week, one “Super Dwarf” (Animal C) was fed twice a week, and the Mainland (Animal D) was fed once a week. All meals were approximately 25% of the animals body weight.

Animals A, B, C and D are always displayed from left to right in the below photographs with the tables.

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

70 Grams 85 Grams 106 Grams 622 Grams

70 Grams 85 Grams 106 Grams 622 Grams

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

68 Grams 97 Grams 146 Grams 1026 Grams

68 Grams 97 Grams 146 Grams 1026 Grams

9/12/2005

10/10/2005

11/07/2005

12/12/2005

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

68 Grams 96 Grams 211 Grams 1387 Grams

68 Grams 96 Grams 211 Grams 1387 Grams

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

66 Grams 124 Grams 348 Grams 1969 Grams

66 Grams 124 Grams 348 Grams 1969 Grams

01/09/2006

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

71 Grams 143 Grams 439 Grams 2811 Grams

71 Grams 143 Grams 439 Grams 2811 Grams

02/14/2006

Animal A 1.0 SD - Animal B 0.1 SD - Animal - C 0.1 SD - Animal D 0.1 Mainland

65 Grams 142 Grams 498 Grams 3425 Grams

65 Grams 142 Grams 498 Grams 3425 Grams

Conclusion

While the above results were by no means attained in a scientific fashion, they do give us an insight. They clearly show that, over a 6 month period, food intake does have a direct effect on the growth rate of the dwarf reticulated python. However, despite increased food intake, animal C was unable to match the size and growth of animal D.

So, in short, this test demonstrates that while diet does play a significant part in the allometry of these creatures, the defining factor involved is genetics.

While the above results were by no means attained in a scientific fashion, they do give us an insight. They clearly show that, over a 6 month period, food intake does have a direct effect on the growth rate of the dwarf reticulated python. However, despite increased food intake, animal C was unable to match the size and growth of animal D.

So, in short, this test demonstrates that while diet does play a significant part in the allometry of these creatures, the defining factor involved is genetics.

Toward a Tree-of-Life for the boas and pythons

R. G. Reynolds et al, 2014.

R. G. Reynolds et al, 2014.

© 2010 Serpentexotics. All rights reserved.

Montreal, Quebec, Canada | 514-641-6046 | e-mail: serpentexotics@gmail.com

Montreal, Quebec, Canada | 514-641-6046 | e-mail: serpentexotics@gmail.com